Over the years, our knowledge and ability to treat rotator cuff tears have really advanced significantly. This includes advances in surgical technique, rehabilitation processes, and even training modifications.

Catalyst Physiotherapy sees many clients that report shoulder pain that appears to be coming from rotator cuff pathology. Notice that I just simple say “rotator cuff pathology.” To me, it doesn’t really matter if it’s torn, partially torn, impinged, inflamed, or anything else. The only thing that matters to me is how well you function and how well you move. Can you lift your arm? Can you work or play sports without difficulty?

Still, when people come to see me, all they care about is if their rotator cuff is torn or receiving a specific diagnosis for their symptoms.

Over the years, we have learned that diagnostic tests, like x-rays and MRIs, often don’t correlate with the level of pathology. This has been shown for injuries such as arthritis and disc pathology which people commonly have but experience no symptoms. I have seen films of people with really nasty looking backs and knees and minimal complaints. Conversely, I have seen films of people with minimal findings but debilitating symptoms. So what's worse?

I have been asked on several occasions, “is it possible to have a rotator cuff tear and no symptoms.” I thought this was a great question, so here it is.

We know in elite level overhead athletes that Conner et al showed that 40% of asymptomatic shoulders had rotator cuff tears. I always say that throwing a ball isn’t good for your body! But what about everyone else?

Another article on the subject was published back in 1999 by Tempelhof et al. They studied 411 asymptomatic shoulders using ultrasound and noted that 23% of subjects had a rotator cuff tear. That’s 1 in 4! Pretty significant percentage, but take a look at the breakdown by age:

- 13% of people aged 50 to 59

- 20% of people aged 60 to 69

- 31% of people aged 70-79

- 51% of people aged 80 or above

As you can see, there is a linear increase in the presence of rotator cuff tears as we age. So the answer to my clients questions are now pretty clear.

YES!

How Can You Have a Rotator Cuff Tear and No Symptoms?

Catalyst Physiotherapy really put symptoms and function together. If you have symptoms you probably aren’t functioning well (for example, lifting your arm.), and if you aren’t functioning well, that is essentially a symptom itself. So the question is, how can you have a rotator cuff tear and no symptoms?

The answer has to do with a suspension bridge!

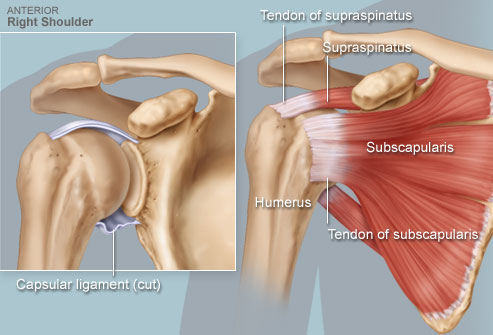

Burkhart et al described what is called the suspension bridge concept of rotator cuff anatomy. If you look at the shoulder from overhead, you can imagine a suspension bridge surrounding the humeral head. In this model, imagine that there is a tear of the supraspinatus muscle on the top of the bridge. If the anterior and posterior rotator cuff (the two suspension towers) are intact and functioning well, shoulder function may be maintained. photo from Burhart et al

This explains the massive irreparable rotator cuff tears that we see and can eventually rehabilitate them back to lifting their shoulder again. This also explains why so many rotator cuff repairs fail after surgery, but patients are still satisfied with their outcome. Essentially if we enhance the anterior and posterior cuff’s ability to dynamically stabilize, you can still maintain function with a supraspinatus tear. In layman's terms, Physiotherapy rehab exercise!

So, you can have a rotator cuff tear and no symptoms, you just need a strong and stable cuff around the tear to help dynamically stabilise.